By contrast, “Where I Learned to Look: Art from the Yard” at the ICA Philadelphia, curated by Josh T. Franco, takes two of Chicanx art’s founding aesthetic analyses—rasquachismo and domesticana—and places them in the wider context of Yard Art. For me, this is a natural development and speaks to a wider embrace of Latinx art. While the focus here isn’t necessarily on Latinx artists, the show is grounded in Franco’s experience as a Chicano artist and art historian from West Texas. In the opening wall text, Franco writes that the yard art of his late grandfather, Hipolito “Polé” Hernandez, was the “unexpected training grounds for my earliest exercises in close observation … My grandfather’s yard is where I learned to look.”

read full article here.

“Where I Learned to Look: Art from the Yard” is an act of devotion and confrontation in equal measure. The exhibition features more than 30 works by noted artists such as Donald Judd, Jeff Koons, Noah Purifoy, and Wendy Red Star alongside community-taught artists such as the Bridge Way School Recovery Artist-in-Residence Program, Clarke Bedford, and the Painted Screen Society. The dynamic sightlines and interplay among works in the show, curated by artist and art historian Josh T. Franco as part of the ICA Philadelphia’s Sachs Guest Curator Program, offer an expansive framework for contemplating yard art.

Read full article here.

Conventional art history proclaims Abstract Expressionism as the first originally “American” artform. With all due respect to Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, and the de Koonings, another novel artform was simultaneously developing in post-War America.

It came from Wisconsin and Mississippi and Texas, outside “The City” whose critics, curators and collectors decreed what had worth and what did not. Emerging from the hinterland, this creative expression did not pass their muster. Neither did its practitioners. These artists didn’t attend the Arts Students League. They often didn’t attend any art college, or any college, or sometimes any high school for that matter.

Yard art.

Read full article here.

Whether it’s a set of front steps or a spacious lawn, what you do with the space beyond your walls says something about you. In Where I Learned to Look: Art from the Yard at the Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA), guest curator Josh T. Franco considers what artists express in work made for the outdoors.

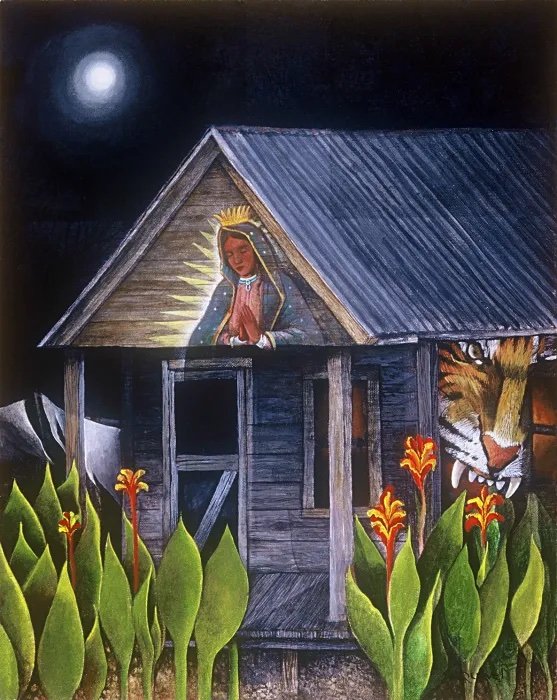

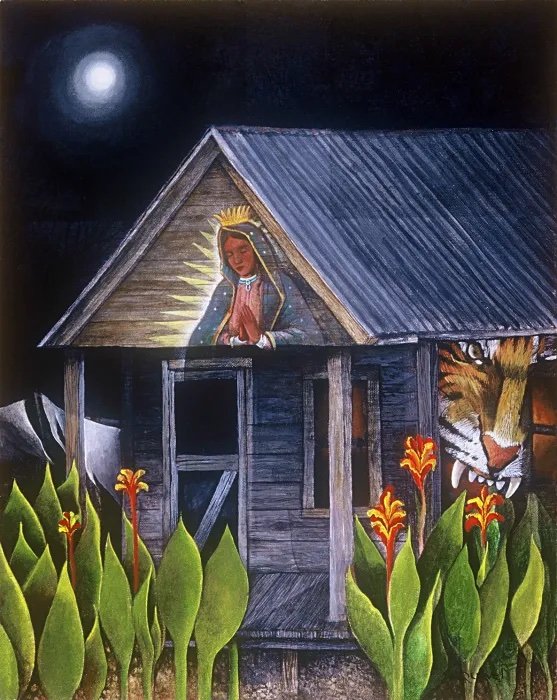

Rasquachismo and La Virgen

Franco’s Preparing La Virgen (2023) leads off the exhibition, which includes 30 self-taught and formally trained creators. Combining film with installation, Franco depicts members of the Sanchez family decorating a shrine dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe in the location where she is believed to have appeared years ago, an area that’s now a neighborhood of tract houses and trailers.

Read full article here.

“Where I Learned to Look” is guest curated by artist and art historian Josh T. Franco and organized by ICA curators Hallie Ringle and Denise Ryner. Franco’s interest in yard art began as an academic one while finishing his Ph.D., but also stems from lived experience: His grandfather, though he never called himself a “yard artist,” would salvage objects and create sculptural vignettes in his free time. His grandfather was particularly fond of a cowboys-themed area he created through stencil forms.

Read full article here.

One of the most striking—and fun—pieces on view in “Where I Learned to Look: Art From the Yard,” which runs through December 1 at the Institute of Contemporary Art, is a handmade contraption that exemplifies what inspired Josh T. Franco, the exhibition’s guest curator, to become an artist and art historian. A whimsical windmill crafted from found objects by his grandfather, Hipolito “Polé” Hernandez, it’s a prime example of “yard art.” Often made by untutored artists, such works—adorning backyards, porches, and driveways across America—expand the idea of who gets to create art, and where it’s displayed, Franco contends.

Read full article here.

Where I Learned To Look: Art From the Yard, curated by artist and art historian Josh Franco and organized by two ICA curators, Hallie Ringle and Denise Ryner, is the exhibition on the ground floor. Placed as though it were a front yard of a home, the exhibition sees Franco examine the practically quirky, adoringly sentimental, and handmade work of yard art. Within a collection of over 30 works by varying artists, paintings, videos, sculpture, and assemblage represent the yard, a space which Franco describes on the wall text as “a patch of grass, a strip of sidewalk, a fencepost, the open woods, or even a notebook” and a transition “between the home and wider world.”

Read full article here.

Clark Bedford moved his ancient, trash-packed Volkswagen out of his Maryland driveway — and into a contemporary art gallery.

“Art Car,” the junk-adorned car that Bedford built to bedazzle his otherwise boring suburban neighborhood, is part of the exhibit Where I Learned To Look: Art From The Yard, currently on display at University of Pennsylvania’s Institute of Contemporary Art.

The one-room show, curated by artist Josh T. Franco, is like a turbo-mode roadtrip across America.

Read full article here.

West Philadelphia’s Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) is an iconic minimalist space renowned for white and glass exteriors and cool linear insides. Starting July 13, however, ICA opens its doors and its floors to the mossy, messy, eclectic exhibition ‘Where I Learned to Look: Art from the Yard.’

Here, 30+ artists display the “lineage and legacy of yard art” while adding their own fresh, funky perspectives as to what yard aestheticism brings to the weight of contemporary art. Curated by artist and art historian Josh T Franco, this exhibition presents the idea of one’s grassy knoll as an “intermediary space between public and private” that artists use for self-expression.

Franco sat down with Metro to talk more about inspirations, possibilities and why yard art is so special.

Read full article here.

Artist and writer Josh Franco grew up in West Texas, where his grandfather used to make whimsical things out of found objects in the yard.

Hipolito Pole Hernandez, who died in 2015, did not call himself an artist. He just liked to make stuff.

“He had three little sheds in his backyard that were his workshops,” Franco said. “There were always sculptures, altered objects, all kinds of things coming out of them.”

Hernandez found a small windmill, painted it pink and affixed animal silhouettes: a hawk swooping down on a snake hovering next to a rabbit and a rooster. It describes a story, of a sort, about natural predators.

Franco included “Untitled (windmill)” in the exhibition “Where I Learned to Look: Art From the Yard” at the Institution of Contemporary Art at Penn, alongside other makers — so-called “outsider” artists who are not formally trained to giants of the fine art world, like Jeff Koons.

“One of the central questions of yard art, as a scholarly field, is ‘Why?’” he said. “Every artist has their own articulation of why they do it. In the text for the show we’ve used ‘world building.’ The one thing you can say that everybody shares is an impulse to build their own world.”

Read full article here.

The exhibition opens with Franco’s installation from which the exhibition takes its name. On the floor is an arrangement of votive candles set on a semi-circular bed of gravel, bordered by tires cut in half to create a decorative edging. It provides entree to his grandfather’s garden, which is the subject of the video projected on the back wall. The video’s overwritten narrative is in both Franco’s voice and that of the Virgin of Guadalupe, to whom his grandfather’s altar is devoted. She compares the response of Franco’s family and friends to her altar with those of the visitors drawn to Marfa by Judd’s work; the family members bring her offerings, she says, while the Chinati pilgrims take photos. Franco himself has a foot in both worlds.

Read full article here.

The Syracuse University Art Museum will host artist and art historian Josh T Franco in residence at the museum and on the Syracuse University campus to activate “Scriptorium con Safos: Syracuse,” and to engage with the community. The mini-residency is sponsored through generous support provided by Art Bridges.

Read full article here.

Dear Josh T. Franco,

We do not know each other and it appears that even despite the fact that we traverse many of the same kind of different worlds of Chican@s, artists, writers and so forth, we do not have any “friends in common” etc. I have to say I find a bit of comfort in this fact; that we can still not know people in a world that is ever-growing-yet-somehow-ever-tiny.

My name is Irina and I was raised mostly throughout the Pacoima-Arleta region of Los Angeles. Throughout the 40’s and 50’s, Pacoima was known as a place that was a safe haven for Mexicans and other farm working peoples. After much roaming and migration, I am fairly certain my family settled there because of this, because of the need of wanting to stop moving. I think about this as I sit with 20-some other artists and writers, all who have or will consider travel quite a bit as the job and lifestyle requires us to do so.

It is also important to know that I come from dreamers. My grandmother Dolores, who I was mostly raised by has always believed that our dreams are powerful tools for our waking moments on earth...

by Irina Contreras

Read full letter here.

Photo: interior, city hall, Marfa, TX, Richard John Jones

Serving up "Instant facul-Tea" with art history lecturer Josh Franco.

By Bethany George, Jaclyn Cataldi

Published: September 3, 2014

See video here.

"A pilgrimage to Marfa is a must for any contemporary art aficionado.

"The trek to the small high desert West Texas town to visit the Chinati Foundation — the singular art museum conceived from a 340-acre former Army facility by Donald Judd — becomes a qualifying badge of sorts, a way to let others know of one's dedication to and appreciation of Judd's heady vision of a place where as he wrote "contemporary art (can) exist as an example of what the art and its context were meant to be."

"The exclusivity of Chinati is undeniable: Marfa is nearly 200 miles from any commercial airport and about 80 miles from an interstate highway. And yet the disconnect between Chinati and its fashionable international visitors, and the longtime Marfa residents, remains profound.

"It's that disconnect that fascinates artist and art historian Josh T. Franco. And he pokes and probes those parallel communities in "Marfita," the clever and slightly irreverent installation he's created along with Alison Kuo and Joshua Saunders at Co-Lab Space."

Jeanne Claire van Ryzin

Read the full article here.

"Texas is enormous. The land is mostly desert with its endless sky. The road stretches for miles, causing the optical illusion of infinity, akin to staring at the ocean. Even in winter, mirages appear on the sand and asphalt. Everything here is marked by a contradiction of unpredictability and control.

"Donald Judd’s Chinati Foundation, housed in the remains of the military base Fort D.A. Russell, is comprised of permanent installations by eleven artists, including Dan Flavin, Sol Lewitt, and Roni Horn, which fill the base’s former meeting-houses, infirmaries, and sleeping quarters. School No. 6 by Ilya Kabakov is a fabricated Soviet elementary school classroom where the holes in the exterior walls are left unfilled, allowing sand to blow in, coating an already aged patina. John Wesley’s surreal figurations, dependent on their own odd sense of repetition, stand out as the sole moment of whimsy. Everything was selected and overseen by Judd. A massive installation of his signature aluminum boxes, each with facets in unique configurations, fills two hangars that once housed German prisoners of war. A hand-painted sign that translates: “Use your head or lose your head” looms above the works."

Read the full article here.

From one of the four corners of the flat earth, Fogo Island, in Newfoundland, has appeared on the radar of contemporary art. Recognized for Fogo Island Arts, a residency-based contemporary arts institution with international ambition and connections, art here is inextricably tied to a larger rural renewal initiative to revitalize Fogo Island’s economy through sustainable tourism. The remote, rocky island is rife with lore and history, and the narratives developing around Fogo Island Arts are in keeping with that tradition.

Fogo Island is an outport (the term used for isolated coastal communities in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador) that was settled by the Irish and English in the mid eighteenth century. Its inhabitants have relied on fishing, struggled with dwindling cod stocks, and fiercely resisted a forcible move to a larger settlement as recently as 1967 — all while eking out a hardscrabble existence. Today the island has a population of about two thousand seven hundred, down from a high of six thousand prior to the federal government’s instatement of a cod moratorium in the early 1990s. Analogous to the island’s resilient culture, self-sufficiency is a key aspect of the Fogo Island Arts project. Engaging contemporary art to help reinvigorate a rural and remote community, it is a long way from the art world audience found in more urban contexts. To travel to Fogo Island requires multiple flights, driving, a ferry, and then more driving.[i] It’s a journey. The journey — an art pilgrimage not unlike a visit to Walter De Maria’s Lightning Fields — offers both imaginative escapism and access to experiential knowledge. Even place-names become more fantastical as one approaches Fogo Island: from Vancouver a traveller passes through airports in Toronto, St. John’s, and Gander, drives across a scrubby, densely treed landscape that appears endless, takes a ferry on the Atlantic through a stop at Change Islands, and then once on Fogo Island drives through communities such as Stag Harbour, Little Seldom, Seldom, Barr’d Islands, Joe Batt’s Arm, and Tilting, where along the inlets small, mostly traditional wooden buildings face the ocean in surprisingly dense clusters.

Fogo Island Arts (FIA) undertakes a program that includes not only an artist residency, but also exhibitions, publications, and public programming such as the Fogo Island Dialogues, a three-day event (July 19-21, 2013) with approximately twenty international speakers that sought to focus on how art can influence social change. This program is the first in an internationally promoted series, simultaneously bringing attention to the FIA project and troubling its very premise. The Dialogues belong within a contemporary art system where conversations and speaker series are understood as legitimate and legitimizing discursive practices. Narratives, such as those produced by the Dialogues, result in concentric waves that spread the reach of the FIA project. However, art is not the only background against which the Dialogues play out: its intertwined contexts include business and cultural ecologies, specifically sustainable tourism that relies on national and international visitors, and the maintenance of cultural traditions.

Melanie O’Brian

Read the full article here.

I’ve known Josh Franco for about a year now. He teaches in the Art History department at Ithaca College, and I teach in the Writing Department. We both came to IC under the auspices of the Pre-Doctoral Diversity Fellowship. Josh and I share a mutual admiration for the work of Gloria Anzaldúa, and in teaching the Poetics class this semester I invited Josh to come talk to my class about his involvement with the Society for the Study of Gloria Anzaldúa and about his dissertation, research, and art practice. In awe of his work, I initiated this conversation with him via email, which I am so excited to share with all of you.

"The U.S. Latina/o Art Forum has just put out a call to action for all its members, urging them to “increase the representation of Latinx art at the 2017 Annual [College Art Association] Conference by submitting a proposal to present a paper.” The appeal was made by the associate director of the Forum, Rose G. Salseda, and a student member, Mary Thomas. Salseda and Thomas founded this call on their analysis of Latino/a representation at the Annual Conference of CAA between 2012 and 2016."

Seph Rodney

Read full article here.

Writing about Josh T. Franco’s work “In Tlilli, In Tlapalli: Three Tejanos in Red and Black,” Rotem Rozental follows the migration and reincarnation of individuals, colors, ideas, and legacies between New York City and Marfa, TX.

Read full article here.

Selected cascarones from Impurity takes huevos y reading con cariño (for María Lugones), an installation and collaboration with Chris Oliver, were included in the event honoring Lydia Cabrera, folklorist.

See more about the event here.

by Kathleen Shafer

"This inviting book explores how small-town Marfa, Texas, has become a landmark arts destination and tourist attraction, despite—and because of—its remote location in the immense Chihuahuan desert."

See citations here.

Artists, Writers Gather in New York to Summon the Spirit of Donald Judd Through Marathon Reading

“Most know Judd, who died in 1994 at the age of 65, for his art, but his writing is equally famous among a die-hard crowd. Brick-like tomes of his writing and interviews have been put out regularly by the foundation, and his criticism has been published by art periodicals such as the one you’re reading right now. In some ways, Judd was more prolific as a writer than as an artist. He also gave numerous interviews, so it required a full afternoon even to scratch the surface of them. On tap this past weekend to read some of them—which are newly compiled in a 1,050-page book—were artist Josh T Franco, Flavin Judd (named after a different Minimalist, Dan Flavin), curator Juliana Steiner, ARTnews executive editor Andrew Russeth, critic Phyllis Tuchman, and writer Fran Lebowitz. Most readers paired off, with one side speaking as the interviewer, and the other reading as Judd.”

By Annie Armstrong

read full article here.

“Less cosmic would be Josh T. Franco’s work, centered on a snake cobbled out of colored stone and splayed on the gallery floor. Step carefully over and through and you’ll develop a sense of communion with the wonder of Franco’s evocations — of ancient cave paintings and wayfinding mechanisms, eons before European explorers ever thought to draw lines on a map. Franco’s work forges a connection — in color, in form, in the ground underfoot — across millennia, then to now. In a set of painted panels on the wall, he quotes Aby Warburg, the German cultural theorist who more than a century ago visited the Hopi tribes of New Mexico, moving him to see modern European culture as a blip against the vast arc of Indigenous practice despite centuries of attempts to destroy it. “It is only the contact with the new age that results in polarization,” he wrote.”

by Murray Whyte

read full article here.

“The most refreshingly disruptive of the offerings, particularly in the formal setting of the Addison Gallery, is an immersive reading room entitled SNAKE ATLAS (serpent lightning leads to water; for my father who was bitten, so that rattler also resides in me) by Josh T. Franco, a Chicano and Texan who currently lives in Maryland. The room has a warm and abundant feel accentuated by an upbeat, rollicking sonic land-scape made for the installation by ambient/experimental musician Chad Turner. The stimulating combination of materials includes handprints upon corn husks, art historical quotes upon a painted grid of 35mm projector slides, and even a rattlesnake head in a jar (an artwork by Robert Smithson) on a shelf flanked by pieces of gold quartz and golden obsidian. In an elaborate, map-like drawing, a handwritten passage from Cormac McCarthy’s 1985 novel Blood Meridian encompasses the pictograph of a horse and rider, further bordered by engaging marginalia, including a phrase that is part of the work’s title, “fuck the Judge.” The star of the room is a large snake sculpture made with thousands of multicolored marble chips. Snakes traditionally lead desert peoples to water, so sighting one would be of more use than a map. It is the only work in the exhibition to refer directly to the earth by bringing pieces of it inside and placing them back upon the ground.”

by Shana Dumont Garr

read full article here.